A few years ago, I was really stuck. I had accepted a one-year consulting contract that required me to commute from Austin to Los Angeles. It paid very well, but the gig was a disaster.

Everything was in chaos. No one could get anything done. We were at the complete mercy of a Wall Street hedge fund and a bunch of lawyers who were battling for control of the company.

I was frustrated. After I ran into a brick wall multiple times, it was like learned helplessness. What could I do? What was the point? I decided to just sit there and collect my checks while I waited for my contract to end.

Then I remembered a piece of advice I had gotten from the author Robert Greene many years earlier. He told me there are two types of time: alive time and dead time. One is when you sit around, when you wait until things happen to you. The other is when you are in control, when you make every second count, when you are learning and improving and growing.

Robert knows a lot about alive time and dead time. Although most people think of him as an incredibly productive and accomplished writer of amazing books, they don’t know about the 20 years he spent in obscurity, working something like 80 different jobs — most of which he hated—where he was at the mercy of horrible bosses.

As he said, “The worst thing in life you can have is a job that you hate, that you have no energy in, that you’re not creative with and you’re not thinking of the future. To me, might as well be dead.”

This does not mean you should quit your job immediately if you don’t love it. What Robert did during those years greatly influenced his writing. He wasn’t dead in those dead-end jobs; he was alive — researching, learning, studying, and observing the forces he would document in 48 Laws of Power, The Art of Seduction, Mastery, and The Laws of Human Nature.

So I decided I would make the absolute most of every moment while I was stuck in L.A.

I could not control what was going on with the board of directors, but I could choose how to spend my days. I decided to make the next several months a kind of work-study program. I was going to learn everything I could about people, about myself, about the factors that had created this crisis. I was also going to fill every nonworking second with productive reading and research.

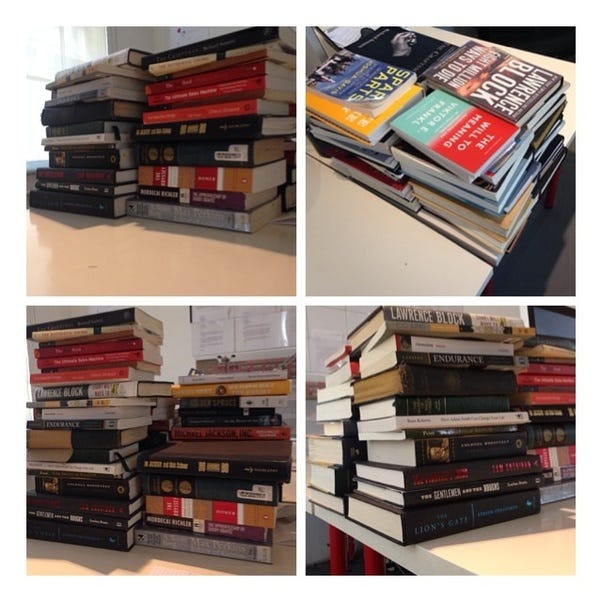

Here is my desk and the books I read in that time (compare that to a shot from earlier that summer):

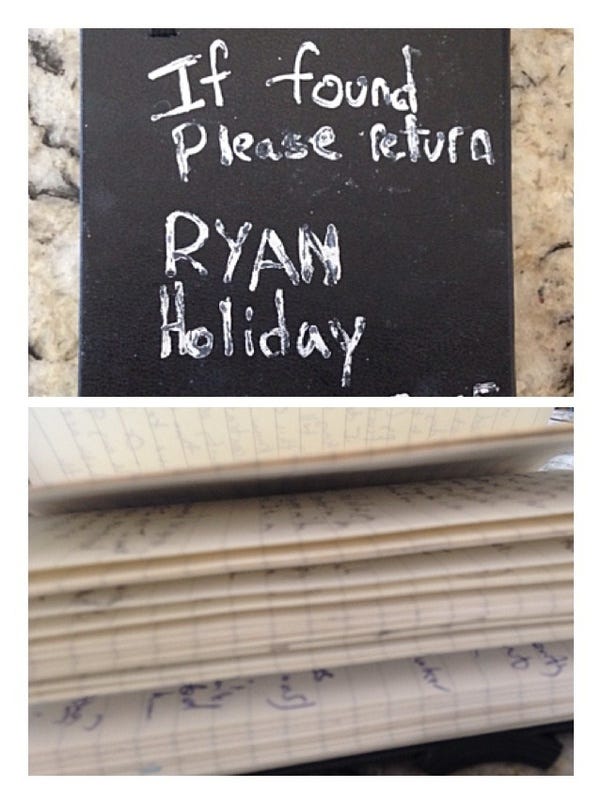

Here is the notebook I filled, writing a daily note to myself (I decided I would open the journal every day before checking email).

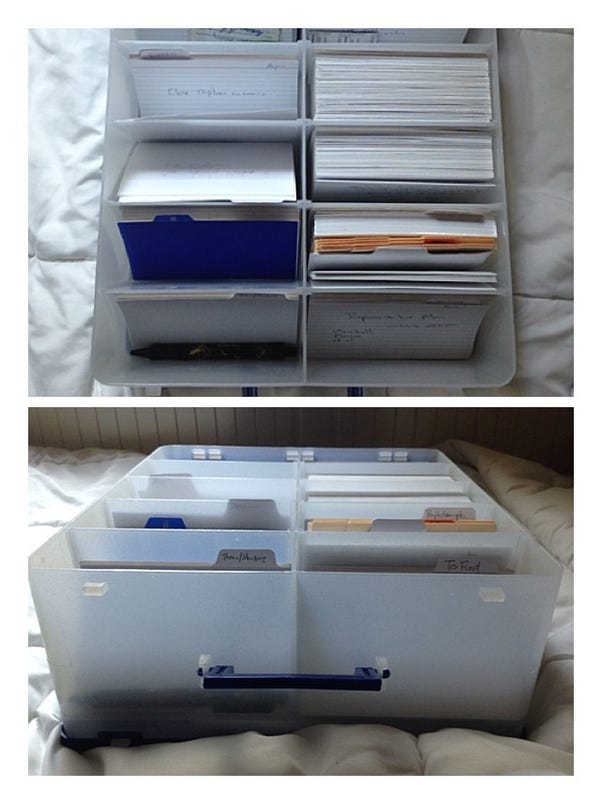

Here is the box of notecards I filled. I am most proud of the second box because these notes became my book, Ego is the Enemy.

As frustrated as I was with that consulting gig, it was actually the perfect place for me to research and meditate on that book I was thinking about writing. (You could say the obstacle was the way.)

Life is constantly asking us, Is this going to be alive time or dead time?

A long commute. Are we going to zone out or listen to an audiobook?

A delayed flight. Are we going to get in a couple of miles by walking around the terminal or shove a Cinnabon into our face?

A tour of duty or a contract we have to earn out. Is this tying us down or freeing us up?

That’s our call.

In Ego, I told the story of Malcolm Little. In 1946 he was arrested for trying to fence an expensive watch he’d stolen. In his apartment, police found jewelry, furs, an arsenal of guns, and all his burglary tools. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. He could have served his time simply counting the days. He could have planned his next crime spree. Instead, he started reading. He literally copied the dictionary word for word. Every minute he wasn’t in his bunk, he was in the library. That was how Malcolm Little was transformed into Malcolm X.

Why did Malcolm X wear glasses? Because he literally wore his eyes out reading in prison.

But the trade-off was worth it. Those five years he served were some of the most productive of his life. He breathed in every second while his fellow prisoners rotted away.

So many people are busy thinking about the future that they miss the opportunities right in front of them. We think the future is something that happens, rather than something we make.

We think, This is just a job; this is just a crappy couple of [months, minutes, weeks]. It doesn’t matter. We tell ourselves that we’re just doing this to pay for school or because we have to. That no good can come out of it, except the direct deposit every two weeks.

I carry this medallion with me everywhere I go…

Like Robert says, if you’re going to think like that, you might as well be dead. Your mind apparently is.

We have to choose to make every moment a moment of alive time. We have to decide to be present. To make the most of whatever is in front of us.

Might it be better if we were totally free; if we weren’t stuck in traffic or at the airport or on some dumb assignment from our idiot boss? Sure. But we aren’t.

So what are we going to do about it? We are going to find some advantage.

Pick up a book. Pick up a pen. Pick up the phone.

Open your eyes. Open your ears. Open your mind.

There is plenty you can get out of this. Plenty you can do to make this productive, purposeful time—even if the situation is not completely in your control.

Resist the temptation to let silly politics or wanderlust distract you. Resist the resentment or the despondency. These things won’t help you. Only hunger and determination will.

In the 1960s, French political protesters used the slogan Vivre sans temps mort(live without wasted time). That’s what great leaders and artists have done, even in terrible conditions like a prison sentence, an exile, a bear market or a depression, military conscription, even being sent to a concentration camp (see Viktor Frankl). Through their attitude and approach, they transformed their circumstances into something that fueled greatness.

They asked themselves, alive time or dead time? They answered with their actions. Can you?

As they say, this moment is not your life. But it is a moment in your life. How will you use it?