Buried in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Crack Up, a collection of the great writer’s essays and diary entries written during his sad decline, is a quick mention of a fellow alcoholic writer and a book about his struggles.

He doesn’t mention the title. He doesn’t explain anything about the author, William Seabrook, besides his name. Probably because at the time he wrote the essay, both things were self-evident. William Seabrook was, at least then, much more famous than Fitzgerald.

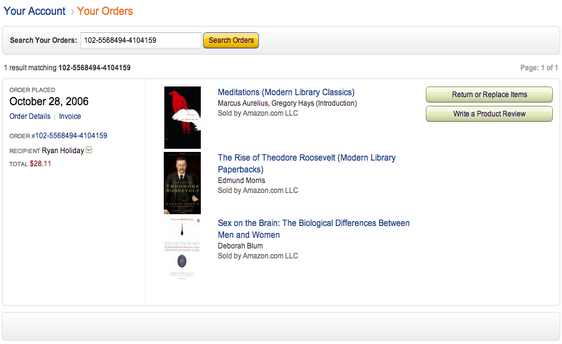

I remember coming across this mention and making a note of it. I looked for the book on Amazon a few days later. The only copy available was a Bantam paperback from 1947. It cost $13.98 with shipping. (Today it starts at $75.00.)

Little did I know, the book that would arrive would become one of my all-time favorites and that I would play some role in not just helping it find a new audience, but bringing it back into print after decades in obscurity.

That book? Asylum (An Alcoholic Takes the Cure)—the very true story of the journalist William Seabrook who, in December 1933, as one of the most successful travel writers in the world, committed himself voluntarily into an insane asylum to treat a crippling addiction to alcohol. In a time before 12-step programs, support groups and rehab centers, there were no other options. What emerged was not just quite possibly one of the first modern addiction/recovery memoirs, but perhaps the most honest and haunting accounts of the struggle for mental health in literature.

A travel book where the journey is inward instead of outward? You can write like that? You can look at your own problems and your own role in them like that?

You cannot turn a page in the book without watching him bump, unknowingly, into the basic principles of 12-step groups and the patterns of behavior we now associate with depression and addiction. Trapped behind the walls of the institution, Seabrook wrote:

I was forced to see sober a panorama that had been nothing but a miserable series of “runnings away from myself” since earliest childhood, and in which I now fully realized for the first time, neither whiskey nor the particular trade I had adopted were anything more than incidental. I took sober stock and saw that dissatisfaction, a sense of my own inability to arrive at a harmonious adjustment in any environment—sporadically dotted with flights and attempted escapes—had been the whole pattern of my life. I had run away ineffectually at 6 to be a pirate as all children do, and instead of getting maturer powers of adjustment as I grew older, I had been running away ever since… Now I knew that all the time I had been running away from something, and that the thing had always been myself.

Like many busy, successful people, Seabrook’s busy-ness and success were as much aresult of his addiction as his addiction inhibited them. Addiction doesn’t immediately drive us to rock bottom, sometimes it takes a detour to top of the mountain first. In fact, it was only when Seabrook had his fame and career and many bestselling works—a writer with enough money in the bank can be a dangerous thing—that the toll of his behavior finally began to make itself known. Only then did the impostor syndrome begin to creep in (and in shame, he began to drink heavily to pretend it wasn’t true).

Always ahead of the curve, he was a modern man right before modern times. Which is what makes this book so powerful, so timeless, so provocative then, as now. And yet, despite the splash this book made at the time, the book was eventually forgotten and lost to history. Seabrook was too, despite his significant contributions to American culture. This was the man, after all, who gave us the world “Zombie” and was notorious for having eaten human flesh and writing about it. How could he have been forgotten while the works of other lesser writers remain? I’m not sure.

All I know is that when I read the book, I was blown away by its vulnerability and honesty. A travel book where the journey is inward instead of outward? You can write like that? You can look at your own problems and your own role in them like that? In retrospect, a lot of the most insightful observations went over my head—but in the way that the gonzo journalism of Hunter S. Thompson is so powerful to college freshman, so was the writing of William Seabrook to me.

A few months after reading it, I decided I would start a newsletter specifically to recommend obscure or forgotten books like this. About 100 people signed up. The works of William Seabrook were the first books I recommended. My recommendation read:

From the perspective of a travel writer, [Seabrook] described his own journey through this strange and foreign place. On a regular basis, he says things so clear, so self-aware that you’re stunned an addict could have written it—shocked that this book isn’t a classic American text.

I think I sold about 5 copies.

But over the years that list grew. Where the first group of subscribers nearly seven years ago was small enough to drop into the bcc field in Gmail, last month’s listwent out to more than 50,000 people. A few years ago, I wrote an article for Thought Catalog titled “24 Books You’ve Probably Never Heard Of That Will Change Your Life.” Number 14 was Asylum. The piece was read by about 100,000 people and then more when I reposted it on my own site. It was turned into a SlideShare (200,000 views) and a Business Insider piece (640,000 views) a while later. I once brought the book with me when a client was appearing on Dr. Drew’s show Loveline, but couldn’t bear to part with my only (note-filled) copy.

In any case, over the last few years, Asylum started to get some of the attention it deserved. I’ve heard from hundreds of readers who loved the book. I would see it pop up on Amazon in the recommended books on the pages of some of my favorite authors. Now, when you look at Asylum on Amazon, the “You Might Also Like” section is entirely filled with other books from my list of “24.”

(Photo: Ryan Holiday)

Still, last month I was surprised to get an email from an acquisitions editor at Dover, a publisher that specializes in out-of-print and public domain books. With the help of Seabrook’s son, they were bringing Asylum back. And not just Asylum either—they were going to put multiple editions of his books “into the hands of a new generation of readers.”

A few days later, the book arrived. It has a new cover designed by the illustrator Joe Ollman and a comic that serves as its introduction. I re-read the book and fell in love all over again. It was exactly as I remembered. Insightful, vulnerable, funny. And in the years since my first reading—with my own struggles with forms of addiction and my own personal issues—I took more out of it than I had before.

As a reader and a lover of books, in many ways this is the dream. That one could stumble upon a book randomly, advocate for it and take pride in having paid it forward enough that the book is given a second life. It’s what Bukowski did for Fante and or Walker Percy did for John Kennedy Toole.

I was even able to spend some time on the phone with Seabrook’s son, Bill. Bill told me about the book’s unique path to re-publication, which began with his mother’s smart decision to maintain the book’s copyrights over the years, and continued with the work of the literary agency Watkins/Loomis, which itself is over 100 years old(and also represents writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates). He and I talked about what his father must have been looking for as he traveled to the far corners of the Earth and to the bottom of a bottle on his way to the darkest depths of his own psyche. We spoke about how that same wanderlust—though perhaps without the darkness—was passed from father to son, as it so often seems to be.

The whole thing was almost too perfect.

It’s that sense…that if some people had just had their act together a little more, it could have all turned out even better, even bigger.

I don’t want to say it is perfect because from a publishing perspective the new edition leaves something to be desired. I do wish that Dover could have taken the time to give the book a full introduction that explains to modern readers just who this great man was and why his writing deserves to be known. Having purchased a handful of Dover Thrift editions of books over the years (which Amazon tends to recommend due to their price), I’m familiar with their—let’s just say “economical”—approach to re-publishing famous works. If Penguin Classics or Library of America are the Whole Foods of book publishing, handcrafted, lovingly produced and expertly marketed, then Dover can sometimes feel like the bargain bin at Walmart.

The new cover is cool—but I can’t help but think the book would have been better served by something more subdued. Somehow they lost the book’s helpful subtitle/logline and on the back, gave even less description than the cheap pulp paperback of the mid-20th century. Just compare The Crack Up (published by New Directions) and Asylum and tell me which one you’d rather read.

As one of the book’s biggest and most public fans, I was sad to hear about it onlyafter it was out. The things I would have done for free to help this book! Nor can I be the only one. It’s that sense—common in interactions with the publishing industry—that if some people had just had their act together a little more, it could have all turned out even better, even bigger.

But as anyone who knows the arc of Seabrook’s story can tell you,“almost too perfect” is probably fitting. Because his time at the insane asylum ended in 1934 with a diagnosis that he’d been “cured” of alcoholism. His doctors’ only post-treatment plan? They asked him to promise not to drink for six months.

Seabrook lasted a little longer than that, published his book, moved on with his life and, of course, had his only son. Though eventually, with the approval of the naive medical opinion at the time, he began to drink again. And then moved on to drugs and increasingly dark sexual behavior.

He died in 1945 of an overdose in Rhinebeck, N.Y.

His perfect work and his perfect story disappeared with him.

Until now.

This post appeared originally on the New York Observer.

Like to Read?

I’ve created a list of 15 books you’ve never heard of that will alter your worldview and help you excel at your career.

Get the secret book list here!