Writing gets all the attention and all the glamor.

Young aspiring writers love the story of Jack Kerouac, who supposedly wrote On the Road in a three-week drug-fueled blitz. What they know less about is the six years he spent editing and refining it until it was finally ready.

There’s a similar blind spot in all the creative fields. We listen to artists like Adele, who is famous for titling her albums after the age she was when they were made, and then we hear 25, but are too distracted by the fact that it sold 3.38 million copies in its first week to realize that it actually came out when she was 27. We gloss right over the discrepancy. As creatives, we don’t want to ask why it took two years longer than expected, because the answer might be as difficult to hear as the creative process can be to complete.

In Adele’s case? It was because her producer, Rick Rubin, had all but rejected her first submission of the album. “I don’t believe you,” he said after listening to it. There wasn’t enough heart in it. That undefinable, unquantifiable thing that made her first two albums, 19 and 21, so transcendently great simply wasn’t there. It took Adele two years longer to get the album to a place where Rubin believed her. And where she did too.

As a culture, we love flashes of inspiration and we love finished products. We have little interest and little understanding, however, of what goes on in between—of the essentialness of editing and improving and tweaking until whatever we are creating is just right.

But all the greats loved that space. That’s where they lived. That’s where they were most alive.

And that’s where you have to get comfortable as well, to create something of meaning and lasting value.

Why?

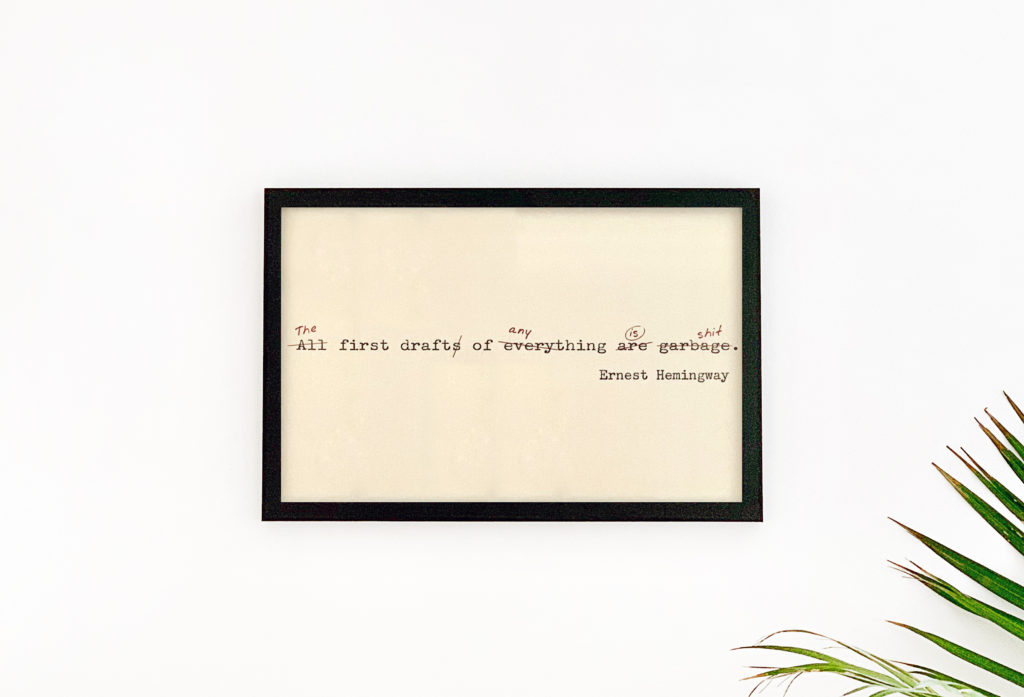

The famous Hemingway line on writing:

Although creators often dream of a world where no one can tell them what to do and where they get to release everything they make, this fantasy would actually be a nightmare. Because our first effort is rarely good enough. We are too close to our work to see it objectively. And whether we like it or not, the obstacles we jump through as part of the publishing and production processes are what make the work better.

Every creative medium has its own version of the editing process.

Authors submit their manuscript to an editor. There is no The Sun Also Rises or The Great Gatsby without Max Perkins.

Screenwriters attach producers with whom they develop a project. There is no Donnie Darko or Get Out without Sean McKittrick.

Musicians have an engineer, and a producer finishes an album with them (it’s also later mastered). There is no Nevermind or Siamese Dream without the legendary Butch Vig.

Even athletes watch hours of film of their own performance—under the unrelenting analysis of their coaches—before game day. There are not two Michael Jordan three-peats with the Chicago Bulls or the Kobe-Shaq three-peat with the Lakers without Phil Jackson.

All of this is there to take a crappy first draft—a middling first effort—and hone it into something usable. Something brilliant.

Another example: In 1956, a young writer named Harper Lee was given a year’s salary by her wealthy friends Michael and Joy Brown to spend the next twelve months writing the novel she had long put off. The Brown’s have long been considered the heroes behind To Kill A Mockingbird. But really, we know now, that the true hero was Tay Hohoff, the editor at J. B. Lippincott Company to whom Lee sent her manuscript in 1957.

Because as nice and receptive as Hohoff was to the book, she made it clear that, in her opinion, this book would require significant reworking before being published. In Tay’s words, the book was “more a series of anecdotes than a fully conceived novel.” Presumably, Lee’s intention had been to create a full novel, and we can assume she thought she had done so when she delivered the manuscript to her editor. Yet here she was, being told by someone she trusted that she may have failed.

So much in the history of art and culture hinges on moments like this. Faced with soul-crushing feedback or rejection, how does the creator respond? With petulance and anger? With open-mindedness and interest? With obsequiousness and desperation? Or careful consideration that parses the signal from the noise?

It is the creator’s choice at this critical juncture that determines so much—whether the project dies right there, whether it is changed beyond recognition by committee, or whether it is transformed from a decent first attempt into a masterpiece.

Fortunately for all of us, Harper Lee was wise enough to listen. Over the course of several rewrites that took more than two years—effectively producing an entirely new cast of characters and a new plot, while retaining her unique and essential perspective—Lee created To Kill a Mockingbird, one of the great works of American literature.

To the public, Mockingbird had been perfect all along. It’s so pure. So innocent. So heartfelt. That has to be natural right? It wasn’t until 2015, when that first draft was published as Go Set a Watchman, that we realized the truth: Without an editor, without a lot of hard work and a lot of editing, history may have never heard of Harper Lee. She wouldn’t have deserved for us to.

This is true for all the geniuses and masterpieces. Even the ones that came down as stream of consciousness. As a Kerouac scholar remarked on the 50th anniversary of On The Road:

“Kerouac cultivated this myth that he was this spontaneous prose man, and that everything that he ever put down was never changed, and that’s not true. He was really a supreme craftsman, and devoted to writing and the writing process.”

What are the chances that your prototype is perfect the first time? WD-40 is named after the forty attempts it took its creators to nail the working formula. The Great Gatsby was rejected several times. The script for Back To The Future was rejected over 40 times. The script for the Best Picture winner, American Beauty, was revised twice in consultation with the director, Sam Mendes, before it went out to actors, and then when Mendes got into the editing process of the film itself he ended up cutting together something nearly 180 degrees removed from what he thought he was making during principal photography. Precisely zero of my ten books were immediately accepted by my publisher—and they were right to kick them back at me. In being forced to go back to the manuscript, I got the books to where they needed to be. I know that now, but at the time it was infuriating to be told, “It’s not quite there yet.”*

As infuriating as it may be, we must be rational and fair about our own work. This is difficult considering our conflict of interest— which is to say, the ultimate conflict of interest: We made it. The way to balance that conflict is to bring in people who are objective. Ask yourself: What are the chances that I’m right and everyone else in the world is wrong? We’ll be better off at least considering why other people have concerns, because the reality is, the truth is almost always somewhere in the middle.

Every project needs to go through this process. Whether it’s with an editor or a producer or a partner or a group of beta users or just through your own relentless perfectionism—whatever form it takes is up to you. But getting outside voices is crucial. The fact is, most people are so terrified of what an outside voice might say that they forgo opportunities to improve what they are making. Remember: Getting feedback requires humility. It demands that you subordinate your thoughts about your project and your love for it and entertain the idea that someone else might have a valuable thing or two to add.

Nobody creates flawless first drafts. And nobody creates better second drafts without the intervention of someone else.

Nobody.

Not even you.

This was originally published on Writing Routines.

•••

If you’re looking for a way to keep this maxim in mind, Writing Routines recently released a print version of Hemingway’s quote:

“The First Draft of Anything Is Shit”